About The Inn

Designed & Built By George Maher, A Contemporary Of Frank Lloyd Wright

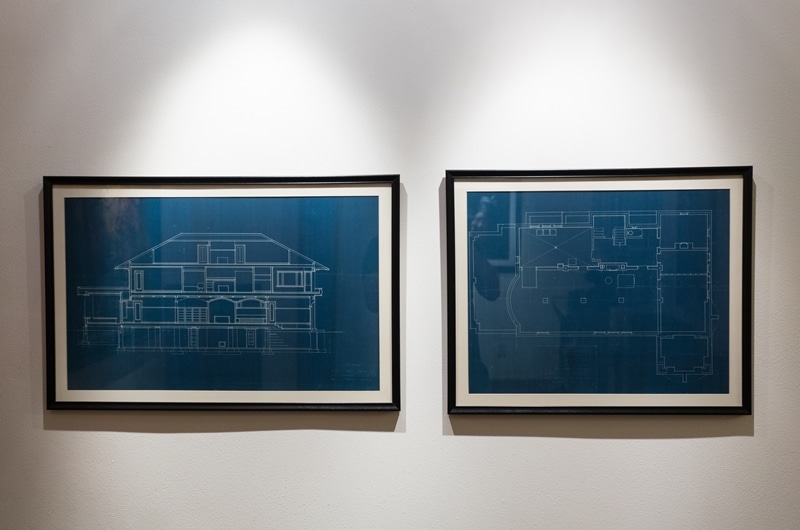

The Stewart Inn was designed and built by George Maher, a contemporary of Frank Lloyd Wright’s and one of the founders of the American arts & crafts movement. It was commissioned by Hiram and Irene Stewart and completed in 1906. The Inn was one of six homes Maher constructed in Wausau (along with two others that he is known to have renovated) and was Wausau’s first property on the National Register of Historic Places.

George Maher frequently incorporated both geometric shapes and botanical elements into his designs. In this instance, the geometric shape was the tripartite (or segmental) arch and the botanical element was the tulip. He repeated these elements throughout the house to create what he referred to as the “motif rhythm theory,” a cohesive architecture style that flows prominently throughout a building.

The Stewart Inn is regarded as one of the finest homes in Wausau and considered the most intact example of George Maher’s architecture in the country. The chandeliers, the stained glass windows, the sconces, the fireplace mosaic, the woodwork and so much more are original and in near perfect condition. Even the second floor guest rooms remain largely true to Maher’s original design.

The Foyer

The grand foyer is a warm and welcoming entrance to the Inn. It features two entrances, a front entrance and a side carriage entrance. Both entrance doors have original stained glass windows designed by Giannini and Hilgart who were master artisans from Chicago that did extensive work for George Maher and Frank Lloyd Wright. The doors and interior paneling are made of mahogany. The interior granite steps are from a local quarry.

One of the most subtle design elements of the foyer is the somewhat obscured doorway that leads guests to the downstairs powder room. At the time of construction when carriages were the primary mode of transportation, the access to a powder room allowed guests to freshen up and still make a grand entry into the house.

The Living Room

The living room, or what was then referred to as the drawing room, is a magnificent departure from Victorian architecture. It’s an expansive room with lots of natural light, beautiful botanical chandeliers and sconces, a coifered ceiling, warm honey oak paneling and a mesmerizing mosaic fireplace. It achieves something which is seldom found in historical architecture, a balance between elegance and tranquility.

The living room is where we host our nightly wine reception. It is a space that is comfortable and accessible to our guests throughout their stay.

The Dining Room

The dining room is where we serve breakfast each morning. It features numerous stunning details, highlighted by the incredible chandelier that hangs above the dining room table. The chandelier was a joint collaboration between Willy Lau, a noted Chicago manufacturer of lighting (an artisan also used by Frank Lloyd Wright), and Giannini and Hilgart who produced the glass. Another architectural detail which frequently attracts visitors’ attention is the cantilevered buffet, or sideboard. Like so many other elements in the house, it utilizes the tripartite shape above the counter surface as well as within the design itself. Perhaps our favorite feature is the East wall which itself is a tripartite arch. Imagine the craftsmanship that went into shaping the wood for the panels, buffet and doors done all without modern tools.

The Reception

The reception room, which today is called the media room, is the room where the Stewart’s staff would have escorted guests to wait until they were greeted by the Stewart’s. It has beautiful half windows that are eye-level with art glass and mahogany woodwork. At one time this room featured a large seven foot high tripartite mirror in the middle of the south wall. While the mirror still resides on premise, we find that our guests prefer a large screen television for watching Packer games than sitting in front of a beautiful, but old, silver mirror.

The reception room is frequently used now by our business guests as a place for offsite meetings. In addition to the television and DVD player, it has a port which can connect with a guest’s laptop.

The Office

Mr. Stewart’s office, presently referenced as the library, is perhaps one of the coziest spots in the inn. While it is relatively small room, it has a large masculine arts & crafts fireplace, stucco walls and warm quarter-sawn oak bookcases. The room also has original sconces and the original chandelier with cigar ventilator. One unique feature of the room is the secondary entrance from the outside. This allowed Mr. Stewart to host business clients without them having to come to the front door.

The Stairwell Landing

The stairwell landing is both a beautiful architectural feature and functional space. The raised structure gave occupants the opportunity to survey the main living areas from an elevated vantage point while simultaneously giving foil to the exterior ventilation system. The ventilation system helped equalize the internal and external air pressure, thereby alleviating drafts. The landing has a beautiful bench seat with tripartite windows above the seat.

The Second Floor Hallway

The 2nd floor hallway is one of the few areas within the home that has seen some modest changes. While the general floorplan remains intact, the hallway offers three less doorways than the original design. The missing doorways went to the sitting room, the linen closet and the main bath. The key architectural features that do remain are the original laundry shoot, the electrical box, the intercom phone and the paired stained glass windows that brings natural light from the back (or servants’) stairwell to the hallway. The other historical detail of note is the French tapestry that was given by George Maher to the Stewart family that hangs above the stairwell on the north wall.

This is a title

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, dolor erat ac accumsan nulla, iaculis magna neque amet convallis. Id donec litora nullam praesent, orci velit morbi eget enim, dui amet nulla tempus mauris. Velit nulla eu volutpat, eget urna amet massa. Enim vestibulum nunc massa, erat vel vestibulum aenean, lacus elit mauris dolor eget, quam vestibulum ipsum non. Tenetur lacinia luctus phasellus, penatibus nunc mauris nulla, volutpat turpis sem ipsum iaculis, sed accumsan velit in ut.

Awesome place to stay! My husband and I stayed in the Fuller room at Stewart Inn on Saturday, October 14th. We were warmly greeted by Sara and given a tour and information about the house. To say the house is beautiful is an understatement. Our room was spacious and comfortable. There is a pillow menu if you don't like the pillows that are already on the bed. A keurig, filtered water, and soda were available throughout our stay. They had games to play, and my husband and I opted to play some cards. At 5 p.m. we met Randy when he came downstairs to offer us a glass of wine, which was delicious. Headed to the Red Eye restaurant recommended by Sara for pizza and it was only about a 10-minute walk. My husband really loved the steam shower, and I enjoyed soaking in the claw foot tub. Breakfast consisted of 3 courses. The first course was yogurt with a fig topping and pistachios, second course was a Monte Cristo with an egg on top, and the third course was a crumb cake with fresh whipped cream and raspberries. I was so full and everything was so good. The worst part about the stay was having to leave.

—Stewart Inn Guest